Marie is kindly letting me reprint an essay she just wrote on Thomas Friedman’s coverage of China in his New York Times columns. She gave a presentation on this last Friday in one of her Beida (PKU) classes.

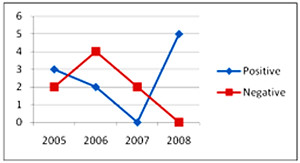

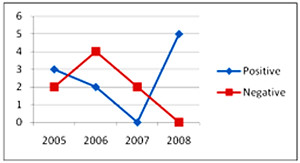

My quick two cents: especially in the light of the hot tempers Western coverage of China often inspires here, I only wish columnists’ views of the Middle Kingdom could be put into such neat graph form as in Marie’s figure 2 below … but if they could, they probably wouldn’t be very good columns. I’ve also a feeling that a lot of Chinese might disagree with that upwards turn in positive reporting she finds in 2007-8.

*

China’s image in Thomas L Friedman’s reports

Introduction

What has been China’s image in The New York Times in recent years? This study attempts to explore the answers to that question by examining China’s image in Thomas L Friedman’s coverage from the years 2005 to 2009.

During these five years, in covering China, Thomas has written more than 150 articles. I choose 36 from these, the most representative coverage of China, try to analyze the content and locate the reasons behind it.

The data is from the New York Times database in the digital library of Peking University. By inputing the key words: AU(Thomas L Friedman) AND GEO(China) AND PDN(>1/1/2005) AND PDN(<4/30/2009), all news which contain China in its headline, or its subject, or its leading paragraph were extracted from the database.

These news items have been classified according to their subject matter, such as Chinese politics, U.S.-China relations, etc. Then they are decoded according to their tones, i.e, positive, negative, or neutral.

1. The overall picture

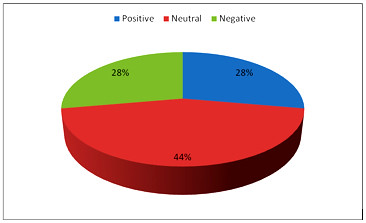

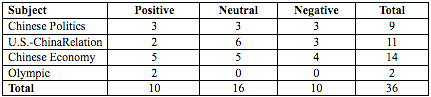

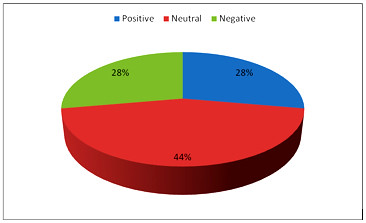

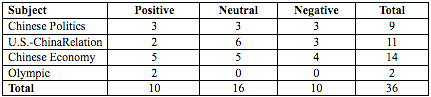

As is shown in Figure 1, during these five years (2005-2009), in covering China, Thomas L Friedman carried nearly as many articles on the neutral side as on the negative and positive sides combined. Table 1 shows the relative importance of various topics in the picture.

Figure 2 demonstrates the changes that the image of China goes through in these five years. It can be seen that positive reporting has experienced an upwards turn in these years.

*

Figure 1 China’s image in Thomas L Friedman’s reports (2005-2009)

Table 1 A breakdown on subjects

Figure 2 The trend of China reporting (2005-2009)

*

2. Chinese politics

About China’s political system, especially Chinese Communist Party leadership, all reports are negative.

For instance, the building of Tiger Leaping Gorge is a huge project in China. Such a thing was interpreted by Thomas L Friedman as a means of “a still heavy-handed Communist Party”. He wrote that “China’s rigid political system leaves these farmers, who are still the majority in China today, with few legal options for fighting it. That helps explain why China’s official media reported that in 1993 some 10,000 incidents of social unrest took place in China. Last year there were 74,000.” The Chinese Government was depicted as “a tightly sealed political lid”.

Lack of democracy was another theme. One example is the lack of transparency, as he mentioned in another report about environmental protection in China. “It requires a freer press that can report on polluters without restraint, even if they are government-owned businesses. It requires transparent laws and regulations, so citizen-activists know their rights and can feel free to confront polluters, no matter how powerful.”

On the other hand, Thomas L Friedman praised Chinese leaders “because their abilities to meld strength and strategy — to thoughtfully plan ahead sand to sacrifice today for a big gain tomorrow.” He pointed out “many of China’s leaders are engineers, people who can talk to you about numbers, long-term problem-solving and the national interest”.

3. Chinese economic conditions

There were so many reports about China’s boom, enough to impress the American readers with the “staggering economic progress” which China has made. This coverage is the least negative. For instance, Thomas L Friedman wrote “The difference is starting to show. Just compare arriving at La Guardia’s dumpy terminal in New York City and driving through the crumbling infrastructure into Manhattan with arriving at Shanghai’s sleek airport and taking the 220-mile-per-hour magnetic levitation train, which uses electromagnetic propulsion instead of steel wheels and tracks, to get to town in a blink.”

For all the achievements, economic problems remain serious in China, such as the problem of rural development, environment pollution, etc. Thomas L Friedman thinks that “Chinese officials still put their highest priority on growing G.D.P. — their bottom line. But for the first time, the costs of this breakneck growth are becoming so obvious on China’s air, glaciers and rivers that the leadership asked for briefings on global warming”.

On the other hand, the Chinese awareness of existing serious problems and their efforts to remedy the problems also found their way into Thomas L Friedman’s reports. The following coverage are good examples: “Postcard From South China”, “China’s Sunshine Boys” , “China’s Little Green Book”.

4. Olympics

The coverage of the Olympics is the most positive. It is perhaps the only major subject about which the positive news greatly outnumbers the negative news.

“China has far outpaced United States in growth during last seven years since it has been preparing for Olympic Games.” He said that wealthy areas were more interesting, advanced and sophisticated than wealthy parts of United States, and attributes this to focus on building infrastructure.

He argued: “US could learn that big, long-term infrastructure projects require intense focus and followthrough(from China)”.

5. U.S.-China Relations

Through Thomas L Friedman’s coverage, we can find that when China’s economy was on high speed of development from 2005 to 2009, U.S.-China relations were very close. He insisted that China would become a “responsible ‘stakeholder’ in the international system.” He hoped that “China and United States can build partnership to address urgent issues of energy and climate change, which affect both countries.” In addition, he points out that nowadays is a “teaching moment” for both of the two countries, which are learning from each other.

Conclusion

This analysis clearly shows that Thomas L Friedman hasn’t been demonizing China. Apart from some sort of distortion of Chinese politics, his reports about China from 2005 to 2009 were more and more balanced.

U.S. domestic politics and culture are different from those of China. How Americans view these differences contributed to how China was portrayed in Thomas L Friedman’s reports. China has embraced the whole world nowadays. I am confident that if Thomas L Friedman really focuses on how ordinary Chinese people live, work, and worship, he will understand China more deeply, even Chinese politics.