|

March 2009

You are currently browsing the monthly archive for March 2009.

I’ve just listened to the Global Humanitarian Forum‘s dialogue on climate justice. It’s a debate discussing how the effects of climate change hit hardest the developing countries which are least responsible – an injustice we must combat. The debate was webcast live to young bloggers around the world on an initiative of the One Young World project I’m part of myself (“a platform to engage and inspire the 25 year olds of today – the decision makers of tomorrow”).

It’s really worth a listen (click the ‘view our webcast’ button on that first link I give). Kofi Annan looms over the proceedings from a telescreen, issuing awkwardly time-delayed warnings while Desmond Tutu cracks jokes from the panel. Tutu also issued, on behalf of his generation, this over-due apology:

It’s your world. And we oldies have made a mess of it, by and large. We are begetting to you a world with a very real, very serious threat of extinction.

The key message of the debate was ‘the polluter must pay’. “Those who are least responsible”, as Tutu put it, “bear the greatest blunt” (like Africa or the Maldives, whose president is rumoured to be looking for a new island in case the current one is submerged by rising water levels), while “the ones who are culprits, for the most part, are able to protect themselves”. A shocking statistic: 90% of natural disasters accur in the global south, where 3% are insured; the other 10% happen in the developed world where 95% are covered.

This is more complicated when it comes to China, of course. China, with it’s vast savings, can pay. And it clearly sees the dangers of inaction: Steven Chu, Obama’s secretary of energy pick, talks in a fascinating interview on ChinaDialogue of how “China already is very afraid. They’re beginning to see the consequences of climate change in their water supplies. In northern China, the Yellow River is beginning to run dry; the Tibetan plateau is melting very quickly”

But action has its risks for China too: of stifling the economic growth and job creation which keeps its countryside happy not too unhappy (I’ll bet a baozi that a provincial government official will choose growth at the cost of the ever-more purple lake next door to the factory every time). So the question is how can we incentivize green energy in China: the kind of companies which in the long-term will drive its economy.

To me, technology transfer seems like the most obvious answer: Western countries like the US (who are historically responsible for climate change) to give developing, polluting countries like China the technologies they can’t afford to – or can but don’t want to – R & D themselves. A stumbling block here is, of all things, China’s terrible protection of intellectual property: this means that US companies are reluctant to disclose their hard-earned techonology secrets for fear of seeing them copied and on sale at Zhongguancun the next week (alright, a bit of an exaggeration).

And a final thought: seeing as Africa is the region hardest hit by, and least to blame for, climate change … will this impact on its relationship with China? China is both hand both behind it’s problems – as the world’s biggest polluter – and the hand feeding it – as an increasingly ubiquitous business partner and funder. If the polluter must pay, shouldn’t China (self-professed responsible member of the world community as it is) take a look at how it’s actions at home are crippling its cross-continental friend?

I’ll be discussing these themes with William. And while I’m here, check out this interesting blog on China and the environment (full disclosure: written by a friend of mine).

UPDATE: William has just emailed me a few quick reactions:

1. Who is the polluter? Companies or consumers? I think the consumer is the polluter, so what what we should do is reduce our consumption. Everyone on the earth should reduce his/her energy use etc. to a certain level (except the poor who have a low emission level). Companies only meet the needs of consumers. Like in this economic crisis, emissions will reduce when consumption reduces.

2. I agree with you in this respect: we should pay more attention to those countries who are least responsible for climate change. But how rich countries can supply their support is a big question.

3. The situation of intellectual property in China is really bad. This makes many foreign companies worry about their economic interests. But technology transfer is necessary, we need to innovate together.

4. It’s a reality that many provincial officials only want to develop the economy and brush over environmental protection. I think that’s why China needs more environmental NGOs.

Tony is a humblingly politically aware friend of mine at Beida (short hand for Peking University). No surprises, I guess, as his dad works in the Foreign Ministry. He’s 21, a Beijinger – grandparents from Hubei – in his third year of a Politics and International Relations course here. And last week, he was secretary general of the United Nations.

Yes, yes, the model UN – where students take on the roles of diplomats of other countries and battle out the issues of the day. It’s incarnation on Chinese soil is held at Beida each spring (they have a website). I first got wind that Tony was this year’s secretary general when I saw him walking across campus in a suit, shuai as Shanghai, followed by a small army of delegates passing him half a dozen mobiles to answer like a troupe of bizarrely up-market phone hawkers.

So I asked Tony to tell us a bit about his experience, in particular how Chinese students react to the diplomatic setting of model UN. He very kindly sent me this long email:

I cannot express to you how delighted I am to see nearly 500 delegates coming from five continents to discuss global issues and exchange their point of views. During a whole year’s preparation, what continuously comes to my mind is a question like this: how can we Chinese students understand ourselves better in this international event? 170 years ago, China was drawn into the tide of globalization. Because of the lack of knowledge about the outside world, the uneasy feeling towards open-up lasts till now. In China, there is a old saying: it is commendable for a man to know himself truly.

But the 21st century is an epoch in which we can only know ourselves until we know the world. The Chinese are now building up new identities through comparison with other countries, through conflict and compromise when dealing with various challenges on the global agenda. This is exactly what we do in the model UN. In China, in fact, the activity itself is on the rise and students are now learning to express themselves according to international rules, trying their best to enter into the common language system, putting themselves in other’s shoes and then look back at their own country.

But I digress. What I would like to share with you is the setbacks faced by Chinese students in the model UN and probably also the obstacles faced by China in becoming a responsible stakeholder.

The Asian International Model UN (AIMUN) is neither an English contest nor a competition in choosing for the best delegate. Many Chinese participants speak fluent English, acquire the rules of procedure and devote themselves in every discussion. But they still face obstacles in communication. On the last day of the conference, a faculty advisor from South America expressed to me her concern that many Chinese delegates speak out of point and always use Chinese during unmoderated caucus, thus forming small blocks in the conference room.

I also mentioned to you last time about the “draft resolution (DR)” issue. In AIMUN, there could be only one DR passed per topic area. For many Chinese students, sponsoring a DR and persuading other delegates to vote for it into the final resolution is a great pride and an expression of the contribution he/she has made in solving a certain global problem. I guess there are basically two reasons why the Chinese care about being the sponsor of DR a lot. Firstly, some students/universities become too utilitarian when it comes to awards.

Many of them take AIMUN a competition held by Beida and their goal is to win the best delegate/delegation award. As an organizer, I understand that many students come to Beijing funded by local schools, so they need to bring a certain “title” home. In fact, many Chinese universities treat it quite seriously as if this is an award given by PKU officials.

The second reason is simple, the Chinese students used to be minorities in model UN conferences. For example, when asked about their experience in Harvard US National model UN, the Chinese participants will often express to you the annoyance of their well-prepared DRs being separated by aggressive Western delegates so that they can never gain the leadership in shaping the final outcome. Though AIMUN is an international conference, most of the delegates are coming from Asian countries. After all, many Chinese delegates think this is a conference held in China and they have some advantages to let others rally around the Chinese flags.

This may seem interesting, but it did give me a headache last week. In 2-3 committees, piles of DRs were of poor quality, conflicts rode over cooperation, but no one would compromise. Last week in our model ASEAN 10+3 Ministerial Summit, when discussing about the pirates in Malacca, two DRs were backed by different country blocks and both were not willing to give in or merge their resolutions with the other. The debate nearly led to personal attack between two Chinese delegates (and in fact, the boy made that girl cry because of his harsh words). Fortunately, they combined the two DRs into a new one because the meeting was coming to an end.

I also found out that Chinese delegates became somehow out of mind when involved in discussions about international law/institutions. That could be explained in some part by the lack of multilateral diplomatic practice of China. This year, we had the UN General Assembly-Legal, which involves 134 delegates discussing international law and global terrorism. This is the largest committee among 12 in AIMUN 2009. In fact, whether we should set up a legal committee this year raised heated discussion among the secretariat, because most of the delegates are not familiar with how a legal committee works.

Not to our surprise, the discussion was not at all “legal” and consensus became more difficult to build among such a number of delegates. But anyway, I think it is a step forward in China to raise university students’ awareness about how IR and international law are interrelated.

I must to confess that organizing international model UN activities is not without embarrassments. I think there’s no need for me to list a few, but some topics are indeed not welcome here in Beida and the school also forbid the association to send delegations abroad when such topics was chosen in other model UN conferences (I remembered the Harvard National model UN once modeled a committee after the 1952 CPPCC and Beida refused to issue students approvals). We also invited 15 delegates representing NGOs in AIMUN, which irritated the university a lot.

The problem is, the organizing committee involves a lot of foreign students in Beida, it is indeed an embarrassment for me to explain to them what is allowed and what is not. Sometimes I am the person who negotiates and compromises with various bureaus, cuts down sensitive topics and lessens the number of foreign delegates in order to make AIMUN survive. After all, it is not that serious like National People’s Congress, right? We are just running a student activity. See if we can discuss these issues next time, Alec. I hope it will interest you as it interests me.

Any thoughts or takes on this? Is this model UN for China’s leaders of tomorrow as important as the National People’s Congress? Do the actions of these Chinese delegates representing foreign countries say anything about attitudes towards multilateral diplomacy in China? Tony would love to hear some reactions, as he is considering writing his thesis on this…

Matilda just taught her first class. She studies techniques of teaching Chinese as a foreign language at Beida (a kind of applied linguistics) and hopes to become a Chinese teacher after she graduates. Her teachers organised this opportunity for her and her classmates to try out what they’ve learnt on real foreign students learning Chinese at Beida. Like me. Indeed, I was in the class.

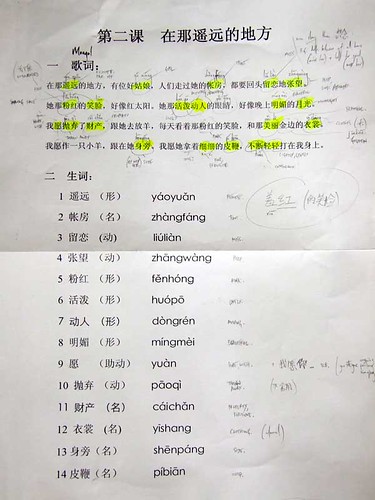

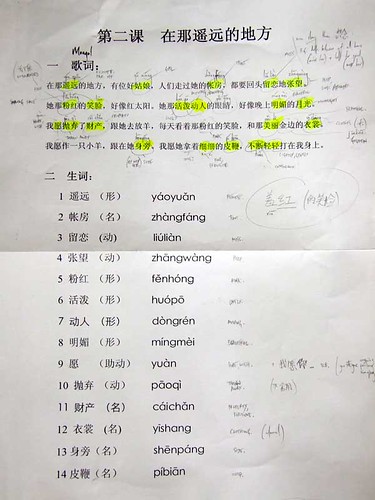

Matilda was clearly terrified at the prospect in the first ten minutes of her class. But she warmed into it. She took a Mongol song from Qinghai province (‘Zai na yaoyuan de difang’: ‘In that far-off place’) and helped us work through the new vocabulary and grammar in the lyrics. It’s a sweet song, if a little culturally ‘different’: the boy in love with the Mongol girl, for instance, wishes to turn into a sheep so he can brush up against the girl’s side every day. I’m sure there’s a law against that.

So I thought I’d post the song (listen here) and the sheet Matilda used to teach us (complete with my scribbles, sorry) so as to add another song to your repertoire beyond Beijing f-ing Huanying Ni:

First line: "In that remote place, there's a beautiful girl..."

Marie studies for over 10 hours each day. From an 8 o’clock start to late at night. That’s perfectly run-of-the-mill in China: and not just at Beida – one of China’s top universities, an equivalent to Oxford or Cambridge – but all across China’s educational landscape, be it university or middle school.

Marie has several friends who have dropped out of Beida after their first year because the stress was simply too much, or took a year off to rest. I’ll try to get some numbers on Chinese students dropping out of college in a future post, as it’s all a bit anecdotal now (though while we’re being anecdotal, compare ‘several’ to only one person in my peer group at Oxford who dropped out).

I asked Marie today how she coped:

There is a question I always ask myself: what kind of person I want to be, and what work I want to have. If I have a goal, I will ignore the tiredness*.

We then touched on why there is such a culture of driving yourself to death at university in China. In haste, here are a four reasons (all fairly obvious) that we came up with:

1. There is more competition in the job market in China. 1.4 billion people and all…

2. Parents have more say in their kid’s choice of university major than they do in the West. And they tend to favour the most demanding subjects as they believe it will improve their kids prospects for employment.

2. A culture of excelling in exams as a measure of your worth can be traced back to the the Imperial exam system (keju) which determined pretty much everything from your job to your haircut for 1,300 years.

3. Back to the parents. If you only have one child, and suffered the cultural revolution in your youth (and couldn’t study at university), there is a tendency to put pressure on your kid to make the most of the opportunities you were deprived.

This is a topic which interests me a lot: I’m likely to return to it. Good night!

___

* As with William and Ben, when I quote Marie it will either be my translation from her Mandarin, or my cleaning-up (grammatically, not content-wise of course) of her English.

It’s not uncommon for a foreigner to give a Chinese friend their English name. I’ve named Ben and William, for instance, and even bestowed the more outlandish names of Ringo and Clement upon kids while in Qinghai two summers ago. I gave Marie (pictured above outside Beijing’s Bell Tower) this French-sounding name, though, not on a whim but because she wants to study in Paris next year. She didn’t like the English name given her by her first English teacher in China: Mindy.

Marie is in her final undergraduate year at Beida, studying Artificial Intelligence: she was one of 18 students in approximately 170,000 in her province to score high enough on her gao kao exams to come here. She’s from southerly Yunnan province, and her roots show in her accent while speaking Chinese. When speaking English she also mixes her ‘l’s with her ‘n’s, which I have never heard another Chinese friend do (‘l’ usually gets confused with ‘r’, thus the undying hilarity of asking for flied lice).

Of course, I’m in position to pass judgment on poor pronunciation. I get the tone of ‘sentence’ wrong, and ask if my tangerine was correct, more often than is polite.

Marie also sexy-jazz dances. Check out this clip to see what that is. She took classes for half a year though, in the the interest of accuracy, she’s now moved on to ‘new jazz’ dancing. When we discuss music, Marie is quick to whip out her MP3 and we listen to Britney Spears (she loves the new song ‘Womanizer’), Avril Lavigne (‘Girlfriend’) and especially the Pussycat Dolls (‘Freak’ is the favourite here … I felt a little awkward when asked to translate the lyrics to this one).

All this in addition to playing the zither-esque guzheng, one of China’s most ancient and traditional musical instruments.

Fingers crossed all will go well and Marie will take her guzheng-worn fingers, 1 in 10,000 exam results, A.I. know-how and sexy/new-jazz moves to Paris in July 2010 to study Physics or Maths. What is it which excites her most about the prospect of living in France, I ask?

“Disneyland.”

This is a conversation I had with William a few months ago, when I was only just getting to know him (and hadn’t started blogging about his life). I can’t remember what turned the flow of our talk in this direction, but William began telling me how lucky he considers himself – being able to work in Beijing for an environmental magazine which involves hard hours but none of the back-breaking rural labour his parents endure:

Only a few people live like me. Most people live in another side, in a factory in South East China [for example] … I don’t need to work hard like them, I read books … In 1.3 billion people, the number of people like me are very small.

I asked him if he misses the countryside he – like so many young guys and girls in China’s capital – is originally from:

William: My parents are peasants, and in my heart, I am a peasant. I have no hukou [registration document] in the city, my ID is in the countryside … I’m not a city person.

Alec: Many peasants come to the city to make more money, there is more opportunity.

William: Make money is not my aim. Having food to eat is enough.

Alec: Your aim is to make a difference?

William: Yes. There are lots of pains in China. I think I should say something [speak out] as a peasant, not a city person. I will be a peasant for my life … In China there are two people: a city person and a rural person.

Well, I think there are two kinds of young immigrants from the countryside in Beijing: those who are all too eager to cut themselves off from their roots, and those who water those roots and keep them in mind (after all, you can change your leaves but not your roots). William is one of the latter. It’s why I consider myself lucky to be his friend.

|

|