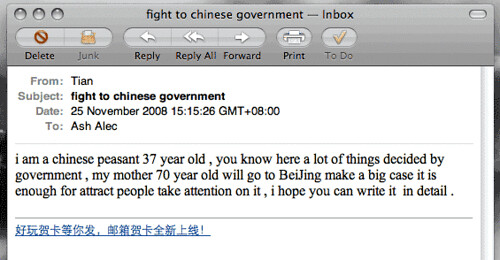

‘Tian’ – one word (most likely the character for ‘heaven’) – presumably found my email address on this blog. He or she mailed me out of the blue towards the end of last month with the below:

Tian's first email

The email of course piqued my curiosity. By ‘make a big case’ I assumed Tian meant petition (the most popular and effective means of protest for those in the countryside to make their grievances known). I wrote a short reply expressing my sympathy and asking for more information. Here is Tian’s response:

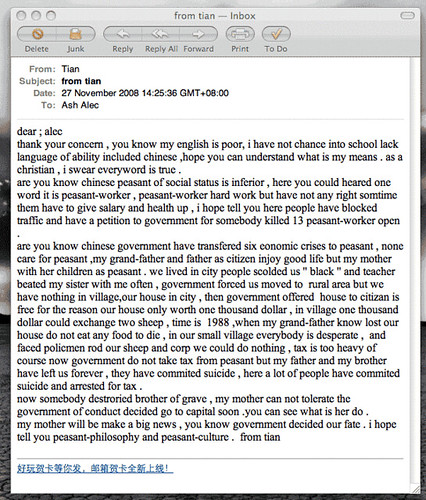

Tian's follow-up, after I asked for further details

I won’t comment too much on this, as I can’t verify the full situation and you can never know (or indeed trust) a person from an email. But here are a few thoughts:

* I see no reason why not to believe this is a genuine attempt to give peasant grievances and Tian’s mother’s planned petition greater publicity. In which case, it’s wonderful that uneducated Chinese read foreign blogs on China (especially one as relatively inconsequential as this one) and view them as a means to get their message out to the world. In a world where traditional publications are on the decline or on the censor’s desk, the blogosphere is the new model for speaking out (this one’s for Jeff Jarvis).

* Tian didn’t answer two of my questions: where is he from? and when will his mother arrive in Beijing? (indeed, to do what, where?) Nor did he reply to my next email, so I’ve no expectations of ever finding out what, if anything, happened. The hopes of peasants who come to Beijing to ‘make a big news’ are all too often crushed by the reality of the petitioning process which is adept at sidelining the issue at hand – or even using strong-arm tactics to sideline the people at hand (as in this tragic story).

* This case (which is too vaguely phrased – ‘somebody killed 13 peasant-worker open’ – to decipher) is only one reminder of the difficulties the majority of Chinese – in its vast countryside – face. Such reminders are always welcome in the comfortable bubble of a foreigner’s Beijing. This month marks the the anniversary of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms: which were a wonderful thing, but the results of them today mean that most peasants have been left behind – overtaxed and desperate – while the industrious, lucky and less unfortunately born few got rich first.

This said, China’s government is working hard to correct this. I wish them luck with it. I for one have never felt more impotent.