|

First, a quote from monk Gyelse Togme’s book The 37-fold Practice of a Bodhissatva, which I stumbled across a mountain-top Buddhist monastery – evidently untouched by tourism – in Qinghai last January:

When encountering objects which please us, / To view them like rainbows in summertime, / Not ultimately real, however beautiful they appear, / And to give up grasping and attachment is the practice of a Bodhissatva.

Now, a photo I took in Yunnan’s all-too touched by tourism Shangri La monastery over my summer holidays, of a business minded monk reading a novel on his break in his shiny new trainers:

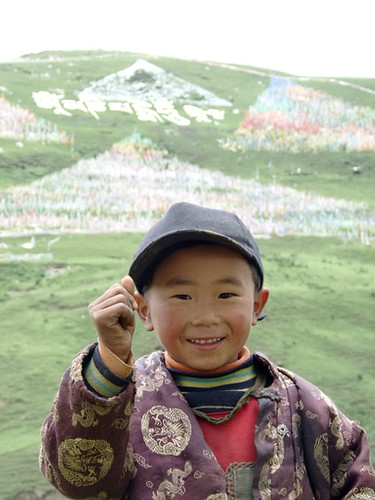

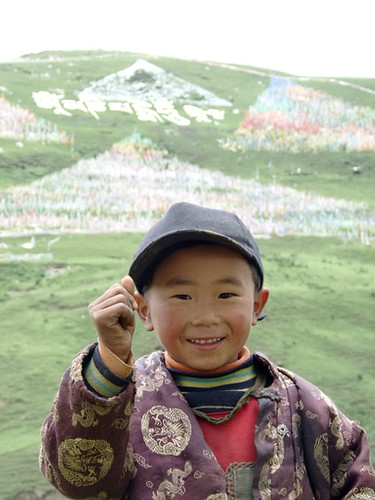

… And a money minded kid by Tagong monastery, Sichuan (beginning to feel the tourist touch, but not half as bad as Shangri La), who asks me for money in payment for me taking his photo:

This at the request of his mum who then crooned at me to take her picture too. These people are not Bodhissatvas but they are without doubt practicing Buddhists. Object away to my pick-and-choose photos. My point is only that as much spiritual dignity is lost in the touristisation of Tibet and material benefit is gained.

I would say Gyelse Togme is spinning in his grave, but he’s been reincarnated, right? Errr … anyway, Gyelse Togme – animal, human, ghost or god that he now is – is probably spinning.

That’s the line from James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon, from where the term ‘Shangri La’ originates:

Seeing it first, it might have been a vision fluttering out of that solitary rhythm in which lack of oxygen had encompassed all his faculties … A group of coloured pavilions clung to the mountainside with none of the grim deliberation of a Rhineland castle, but rather with the chance delicacy of flower petals impaled upon a crag. It was superb and exquisite.

I’m reading the book in Zhongdian, Yunnan – renamed ‘Shangri La’ in 2001 to pull in the tourists. It’s one of several places to claim the name: others are Tibet’s Kun Lun mountains, northern Pakistan, and as far as I can tell pretty much all of Bhutan. All, needless to say, are pretty damn clearly marked on any map.

And as to the Shangri La I’m in (unless lack of oxygen has encompassed all my blogging faculties), I’ve yet to see any delicate flower petal pavilions clinging to the mountainside. I can, however, choose to stay in a hotel themed to look as such for 400 US dollars a night, before stopping in at the monastery, with it’s subway style ticket-swipe gates.

And so, after years of searching, travel worn and oxygen deprived, with only a Western style banana pancake for twenty yuan to comfort me, I have found China’s capitalist Shangri La.

Update: Most of the shop and hostel owners here seem to have heard of Hilton’s novel, if not read it or recognise the name. I learned from one of them, incidentally, that early twentieth century travels and writings of Joseph Rock in this corner of the world might have inspired the novel.

- Yours truly and his humble blog gets a mention from Jeffrey Wasserstrom at the end of his latest Huffington Post article, ‘Illuminating and Misleading Takes on China 20 Years Since Tiananmen‘. Whether I am illuminating or misleading I will leave unclarified for greater suspense.

- I saw Nanjing! Nanjing! the other night in Beida’s packed-to-the-rafters auditorium. I can assure you from the atmosphere at the screening that anger at the Japanese runs deep in this generation, as it has in previous ones. Mind you, the mouth-to-mouth memory of the war seems to have faded enough to allow one group of students a couple of rows behind me laugh blindly at the comedy of a Japanese officer struggling to pull up his trousers … after raping a Chinese girl.

- School’s out for summer, and in a couple of hours – oh joy – I will be boarding a 40 hour train to Kunming. During two weeks traveling in Yunnan and Sichuan, blogging is likely to be thinner than the air at Shangri La.

Below is a new essay for 6 by Jack, with my thanks.

*

The visits of US leaders to Beijing, including Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi and Timothy Geithner, seem to show a fundamental change in Sino-American relations. As The New York Times put it:

China is growing more assertive on the international stage, and Washington is seeking to find ways to cooperate with Beijing on everything from economic reforms to climate change.

Washington is now showing the most kindness to Beijing, the only possible crutch in the eyes of American decision-makers to help the US out of the crisis. All of a sudden, the common model of past Sino-American engagement, that is ‘US pushes – China responds’, appears to be transforming with more weight on the side of China. In my opinion, the financial crisis has indeed heralded a period of transition for the balance of the two countries’ relationship, but a lot of questions are yet to be answered: what will be the result of the change? how long and how big will the change be? Facing such uncertainty, there is no room for complacency for the Chinese. On the one hand, within our capacity, we are facing a challenging task to find solutions to international issues. On the other hand, we should be fully aware of our own weaknesses and address them through deepening reform and opening-up.

First, the US, as well as other countries, expects more from China on the international stage. There are currently three hot issues between China and the US, namely, financial crisis, regional security and climate change. But it is very difficult for today’s China to resolve these problems.

On financial crisis, the US hopes that China could continue to buy its treasury bonds when China’s large holdings of these assets are already on the verge of major devaluation. The US makes money simply by turning on its bank-note printing machine, while China is using the general public’s hard-earned money to buy them. This is not sustainable. But due to the close connection between these two countries, China will also suffer if the US economy collapses. China has proposed to strengthen the importance of Special Drawing Rights and accelerate the internationalization of RMB. How can we strike a balance between short-term and long-term solutions? This is a pressing issue for us to deal with.

On regional security, there has appeared a great uncertainty as DPRK withdrew from the six-party talks and Kim Jung-il identified his successor. In addition, ROK is having a big domestic problem after Roh Moo-hyun committed suicide. How much influence does China have over DPRK? What will happen in Kim Jong-un’s DPRK? Can DPRK and ROK get together again? So many variables are looming before the Korean Peninsula could be denuclearized – daunting and complicated are the tasks for China.

On climate change, the US and China are trying to reach a common understanding before the Copenhagen conference late this year. Currently the 40% emission reduction goal raised by China seems to be too high for the U.S., while the mandatory reduction requirement proposed by the US is unacceptable for Beijing. The two countries are engaging intensively, and hopefully a deal can be brokered at the strategic and economic dialogue late July in Washington. There is an interesting point here. When calculating, China pays more attention to per capita figures while the US total numbers. Everything is small when divided by 1.3 billion, but big when multiplied by 1.3 billion. Based on total figures, China has become the biggest emitter, therefore should do more. However, when using per capita figures, every Chinese person’s contribution to world GHG emission is very limited, so it is unfair and beyond China’s capacity to shoulder the same responsibility as developed countries. A balance also needs to be struck here.

Therefore, in terms of the three biggest expectations placed on China by the US, we wish to do more, but we should not overrate ourselves when making commitments. A well-thought and carefully-crafted balance is badly needed between international responsibility and China’s own interests.

Second, we should always bear in mind our own weaknesses. Thanks to reform and opening-up, China today has much stronger economic power than before. But we are still facing many difficult domestic problems, for example – at the macro level – to strengthen the rule of law and democracy, to carry out economic restructuring, to improve soft power; at the micro level, to address the very problems that the general public hates to see, including corruption, unemployment, and environmental degradation. Some of these problems, if not properly dealt with, may endanger what we have already achieved and destabilise our whole society.

Generally speaking, we cannot be more rational and down-to-earth. China is developing fast, but there is still a long long way to go. We are limited in our capacity and facing numerous domestic problems. China will never seek hegemony. This commitment is based not only on moral grounds, but also on realistic considerations. We should always work hard – there is no room for complacency for the Chinese.

On June 1st, Timothy Geithner came to Peking University and gave this speech. Yes, it’s now the 10th. I waited nine days before posting because 9 is an auspicious number in China, signifying eternity – like the eternal prosperity I wish for Sino-American relations. Obviously.

Two nicely consecutive articles about the speech are the Washington Post’s “Geithner Tells China Its Holdings Are Safe” and the Global Times’ “Geithner’s assurances fall on deaf ears“, which claims such assurances

even drew laughter from the primarily student audience at Peking University, where he studied Chinese in the 1980s, reflecting skepticism in China about the government’s huge holding of US government debt…

What’s for certain is that Geithner was all smiles and telling China exactly what it wanted to hear, whether they believed it or not. The speech clearly must have been mind-numbingly boring to sit through. There isn’t much chance of anything interesting in a political speech given to a country who is bankrolling the speaker’s treasury. Come to think of it, there isn’t much chance of anything interesting in a political speech, full stop.

I’m not the only uninterested one here. Tony and I were chatting about the speech, which didn’t attend (although he was at John McCain’s similarly soporific one on campus last month), partly due to the draconian control on who could get in. The student audience who “laughed” at Geithner were selected by the Office of International Relations (I’d be surprise if the Global Times journalist wasn’t exaggerating the facts to fit his argument). And the questions were pre-selected, reminding Tony of Bill Clinton’s speech at Beida in 1999 – shortly after the NATO bombing – where the questions were supposedly allocated to students by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

All in all, Tony tells me, he can’t bring himself to care much about what Timothy Geithner said. So for anyone thinking the visit of Timothy Geithner sent ripples through the student population at Peking University – whether in reassuring them ala the Washington Post’s headline or angering them as in the Global Times’ – think again. Granted, I’m at the far edge of the Beida pond, but no ripples reached me.

Stay online for an essay by Zhangning which spins off this topic at another angle, after the jump.

From the middle of my exams, a few final bullet points to wrap up June 4th – for those who aren’t fed up to the teeth with the whole umbrella-d business, that is.

- I made no mention earlier of the atmosphere walking around the Beida campus on the big day itself. Well, it was an odd combination of edginess and nonchalance. The edginess came in the form of uniformed police officers circling campus on mopeds (but I only saw a couple, and there was no added security on the gates as far as I could tell). The nonchalance was the utter lack of anything for the police to be policing (despite or because of their presence is another debate – and one already purple with clicked links). I can’t quite make my mind up into which of the two categories the security personnel pictures below fit into: the pair of them were leisurely circling Beida’s infamous ‘triangle’ (the open space on campus where the 1989 students first gathering before moving downtown) all day on their pedal bikes. It was a beautiful summer day, and I would have enjoyed the exercise too.

- To illustrate a point often made that the memory of June 4th is swiftly fading in China’s new generations: I happened to be having a coffee with Matilda that day. After a long chat about other things, I mentioned the occasion. Silence. Errr… blank look. I’m not helping. More awkward blank look. Finally: “Oh yes! I’d completely forgotten that was today”. The generation before, however, needs no jogging. Both my Chinese teacher and the teacher of a friend raised the topics themselves (in a one-on-one and in class respectively), and – albeit in couched terms and swiftly moving on – mentioned how excessive they felt the police action had been this time.

- I just got this email*, in reaction to my earlier post, from the friend whose comments – along with Tony’s – I published in my post about the Sun Dongdong (non) protests:

Some distinguished scholars in China even told me that after one hundred years, people might compare [June 4th] and Deng [Xiaoping’s] reform and opening up with the Zhenguan reign in the Tang Dynasty. Remember both leaders made some tough decisions (they got their hands dirty but the situation forced them to do it that way in order to maintain the public good for the majority; try to understand it in an utilitarian way, too – for them, that is hard to accept but the true meaning of politics) but then initiated the most prosperous and open (comparatively speaking of course) times in Chinese history.

Right. Four anniversaries down, one to go. Then (whisper it) will Zhongnanhai finally tick the last stroke off on it’s giant red zheng and leave us all bloody f-ing alone?

___

* NB: with all the characters I follow on this blog, if they are speaking or writing to me in English I clean up any mistakes in their grammar and spelling before publishing. I’m careful not to change their meaning. Not necessary to mention, perhaps, but shoot me.

|

|