|

May 2009

You are currently browsing the monthly archive for May 2009.

Here’s another offering in the ‘three questions’ vein … this time to Leonidas on something a little less contemporary than NATO bombs (though equally violent?!): ancient China. What I’m specifically interested in is the extent to which young Chinese know and care about classical Chinese literature and language, given China’s breakneck rush to get as far away from its past as possible in the last century.

[A couple of quick notes for anyone who needs them: classical Chinese is different to modern Chinese in both its grammar (think ‘Beowulf’, unless it’s a memory from school you’d prefer to forget) and its characters. Traditional characters are more complex and beautiful than their simplified brethren, for whom they were dumped – like an overly expensive girlfriend – in the 50s.]

*

1. How many young Chinese (not just at Beida!) do you think are familiar with classical Chinese language and literature?

To answer this question clearly, it is necessary to give a definition to the word “familiar”, that is, how familiar can be called familiar? Or, more explicitly, who can be said to be familiar with classical Chinese language and literature. A professor specializing in this field? A student majoring in Chinese language and literature? A person able to recite some classical Chinese works? A person capable of appreciating some classical Chinese works? A standard has to be set, though it is hard, to further the discussion. My standard is that one who is familiar with classical Chinese literature must:

- First, have a command of the common sense of classical Chinese language and literature including the common meaning of the often-used characters, the grammar of ancient Chinese differentiating from that of modern Chinese (these are for language), and basic information on famous writers and poets, and several great works of theirs (these are for literature).

- Second, he can recite some paragraphs or some sentences from these excellent works and know the meaning of them.

- Third, he can roughly understand a certain work with the help of the relevant dictionaries.

By my standard, I think perhaps 10% of university students in China have this familiarity with classical Chinese language and literature.

2. Isn’t classical Chinese just a relic with no real connection to modern China?

Absolutely, classical Chinese is not just a relic. On the contrary, it has a connection to modern China in many aspects.

When one is appreciating a classical Chinese work, he must have some knowledge of classical Chinese. Classical Chinese can tell one the evolution of the meaning of a certain character in modern Chinese, thus making it possible to use it correctly and exactly. Among learned people, classical Chinese is often used in conversation, letters and essays. Even for villagers who have not been educated so much, classical Chinese is also close to their daily life, appearing in the dialects they use, though villagers are ignorant of the fact.

Admittedly, the modern Chinese occupies a much higher percentage in usage than the classical one. However, the latter is in use today and is exerting its influence on the modern life, whether we realize the fact or not.

3. What do you think of the idea of mainland China using traditional characters?

Despite the advocacy from some persons, especially foreign ones, the proposal cannot gain my approval that the traditional Chinese should be used in mainland China instead of the simplified version.

My reasons in favor of simplified Chinese are:

- First, it is easier to learn, and consequently is quite helpful to decrease the rate of the illiteracy in China.

- Second, it has been for several decades and the mainland is used to it.

- Third, it works effectively. It can be written faster and is more understandable due to its simplicity.

Common reasons held by the exponents of traditional Chinese are:

- First, it presents a clearer picture of the meaning of characters. Actually, this is wrong. Most of the characters used in simplified Chinese are different to the ones in traditional Chinese and can also help readers to guess their meanings.

- Second, it is traditional. However, the presumption that traditional is good is doubtable. Even though the presumption stood impregnably, what we use would be “more traditional Chinese” instead of the traditional Chinese proposed. “More traditional Chinese” here means Chinese which is older. In fact, characters used are varying all the time. The characters used in Tang Dynasty were different from the ones used in Han Dynasty. For the people in Tang Dynasty, the latter were of course more traditional than the former, but they chose the former. If we just pursue tradition, hieroglyphs must be the best choice.

- Of course, simplified Chinese is far from perfection, with some flaws remaining in it, for example, the similarity between some pairs of characters. But I think we benefit more than we suffer from simplified Chinese

[NB: that last answer’s in line with what most Chinese netizens are saying, as translated by chinaSMACK. See CDT too]

With enough on our minds already about the day after tomorrow (and I don’t mean the film), here’s a little something on the day before yesterday. May 8th was the ten year anniversary of NATO missiles destroying the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, sparking big protests over here. For more, go no further than the China Beat’s reading list …

So I put three 10-years-on questions to Jack (whose previous essay on this blog has attracted some heated comments). If there were one sentence in the below I had to highlight, it would definitely be this one in his answer to question two:

On the economy, [the West] have been chanting free trade and free market all the time without recognizing China’s full market economy status, but what they really like are protectionist policies and nationalization of banks.

So now it’s the West who are hidden communists?! How things change. Obama, you have your first Chinese criticism for being too left-wing…

*

1. Do Chinese still remember and are offended by this bombing? (Also, do they believe now it was accident or intentional?)

Yes, we will always remember this bombing. In fact, it has been one of the biggest, if not the biggest humiliation to the Chinese people since reform and opening-up.

It was by no means an accident. In my opinion, it was masterminded by the military perhaps without the knowledge of the Clinton administration. Facts speak louder than words. In 1999 NATO bombing of Belgrade, only seven bombs out of more than 5,000 “missed” their targets, and five of the seven were thrown at the Chinese embassy. The five bombs hit the embassy from different directions, destroying the compound. The pilot also paid special attention to the residence of the ambassador, with one bomb precisely hitting his residence. Fortunately, that bomb did not explode. The U.S. was claiming that they had the best pilot, the best weapon, and the best intelligence, so how could they make such a “mistake”? The explanation given by the American side was not convincing at all. They said they used an old map on which the Chinese embassy was not marked. But the truth of the matter is at that time the embassy was marked even on a tourist map of Belgrade. Anyone with a common sense would not believe in their explanation.

After the incident, President Clinton apologized for five times and wrote two letters of apology to President Jiang Zemin. So many apologies made some Chinese people think that maybe it was carried out by the military without the knowledge of top U.S. decision makers. The truth has not been revealed, and perhaps will never be. But based on facts, Chinese people believe it was absolutely intentional, and the only thing unknown is who was behind the attack.

2. What do you believe has changed now in the attitude of young Chinese (like those who protested 10 years ago against the USA) towards America?

Over the past decade, I think the young Chinese have gradually dropped their illusion of the U.S. and begun to view it more objectively.

After reform and opening-up, to be more specific in the 1980s and 1990s, the Chinese people began to know more about the outside world. The prosperity of the west attracted the young people so much that all of a sudden everybody wanted to go abroad. At that time, we had a popular saying, “Moon of the west is even more beautiful than that of China.” Experiencing the sharp contrast between China and the west, many Chinese people became critical of China, perhaps in a cynical way.

However, when the Chinese embassy was bombed, many people began to think: is this the kind of democracy and human rights that we want to pursue? A number of other incidents followed suit, for example, the Iraqi war, Guantanamo Bay, biased report on 3/14 Tibetan incident, which compounded young people’s negative attitude towards the U.S. in specific and the west in general. Many young people tend to believe the west is very hypocritical and has its own weak links. On human rights and democracy, the West does not care about democracy and human rights in other countries at all, and what they care about most are their own interests, for example, oil, geopolitics. And they will bully the weak if the latter do not obey their orders. On the economy, they have been chanting free trade and free market all the time without recognizing China’s full market economy status, but what they really like are protectionist policies and nationalization of banks.

Disillusionment aside, the Chinese have been fully aware of the strength of the west, especially in terms of science, technology and education. Today, still many young Chinese are going abroad for study. And more and more of them are coming back. China is short of qualified professionals. For example, recently the government has adopted a policy to build Shanghai into an international financial center by 2020, but one of the biggest bottlenecks is the lack of talents. Therefore, we still need to learn from the west for our own development.

Generally speaking, the young people in China have gradually turned to view the west, particularly the U.S., in a more objective way. We have become more aware of the hypocrisies and weakness of the west while better understanding their strength. I think this is one of the biggest changes over the past decade.

3. What might happen now if something similar happened again?

First of all, I think the probability of similar incident is very low at present given the higher recognition of China by the west and broader engagement with the west by China. This is a period of transition, from one that China was criticized on many fronts to one that China is expected to take more responsibility as a “responsible stakeholder”. It is vital for China to manage the transitional process by reducing misunderstandings, concerns, or even fears in the west, and it is equally significant for the west to adjust their attitude towards China and “see China in light of its development”.

If something similar happened again, the government and the public would respond in a resolute, serious and rational way. On the one hand, the government would use the diplomatic channel instead of military force. It might impose pressure on the U.S. government for apology and bringing those responsible into justice. It might also stop cooperation with the U.S. in some areas, such as trade, investment, foreign exchange reserve, and so on. Meanwhile, the Chinese government needs to strike a balance between giving the public some space to vent their anger while maintaining social stability and preventing the spread of nationalism. On the other hand, the public would become extremely angry and protest against the U.S., hopefully in a more rational way without throwing rocks at the embassy.

Marie is kindly letting me reprint an essay she just wrote on Thomas Friedman’s coverage of China in his New York Times columns. She gave a presentation on this last Friday in one of her Beida (PKU) classes.

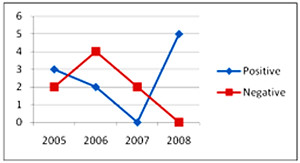

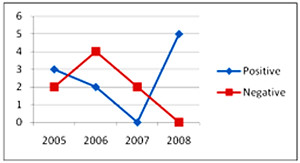

My quick two cents: especially in the light of the hot tempers Western coverage of China often inspires here, I only wish columnists’ views of the Middle Kingdom could be put into such neat graph form as in Marie’s figure 2 below … but if they could, they probably wouldn’t be very good columns. I’ve also a feeling that a lot of Chinese might disagree with that upwards turn in positive reporting she finds in 2007-8.

*

China’s image in Thomas L Friedman’s reports

Introduction

What has been China’s image in The New York Times in recent years? This study attempts to explore the answers to that question by examining China’s image in Thomas L Friedman’s coverage from the years 2005 to 2009.

During these five years, in covering China, Thomas has written more than 150 articles. I choose 36 from these, the most representative coverage of China, try to analyze the content and locate the reasons behind it.

The data is from the New York Times database in the digital library of Peking University. By inputing the key words: AU(Thomas L Friedman) AND GEO(China) AND PDN(>1/1/2005) AND PDN(<4/30/2009), all news which contain China in its headline, or its subject, or its leading paragraph were extracted from the database.

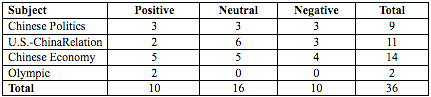

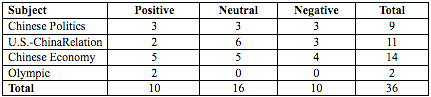

These news items have been classified according to their subject matter, such as Chinese politics, U.S.-China relations, etc. Then they are decoded according to their tones, i.e, positive, negative, or neutral.

1. The overall picture

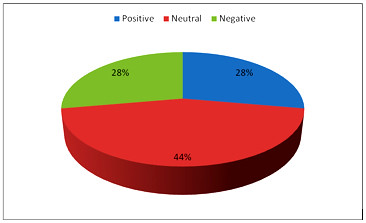

As is shown in Figure 1, during these five years (2005-2009), in covering China, Thomas L Friedman carried nearly as many articles on the neutral side as on the negative and positive sides combined. Table 1 shows the relative importance of various topics in the picture.

Figure 2 demonstrates the changes that the image of China goes through in these five years. It can be seen that positive reporting has experienced an upwards turn in these years.

*

Figure 1 China’s image in Thomas L Friedman’s reports (2005-2009)

Table 1 A breakdown on subjects

Figure 2 The trend of China reporting (2005-2009)

*

2. Chinese politics

About China’s political system, especially Chinese Communist Party leadership, all reports are negative.

For instance, the building of Tiger Leaping Gorge is a huge project in China. Such a thing was interpreted by Thomas L Friedman as a means of “a still heavy-handed Communist Party”. He wrote that “China’s rigid political system leaves these farmers, who are still the majority in China today, with few legal options for fighting it. That helps explain why China’s official media reported that in 1993 some 10,000 incidents of social unrest took place in China. Last year there were 74,000.” The Chinese Government was depicted as “a tightly sealed political lid”.

Lack of democracy was another theme. One example is the lack of transparency, as he mentioned in another report about environmental protection in China. “It requires a freer press that can report on polluters without restraint, even if they are government-owned businesses. It requires transparent laws and regulations, so citizen-activists know their rights and can feel free to confront polluters, no matter how powerful.”

On the other hand, Thomas L Friedman praised Chinese leaders “because their abilities to meld strength and strategy — to thoughtfully plan ahead sand to sacrifice today for a big gain tomorrow.” He pointed out “many of China’s leaders are engineers, people who can talk to you about numbers, long-term problem-solving and the national interest”.

3. Chinese economic conditions

There were so many reports about China’s boom, enough to impress the American readers with the “staggering economic progress” which China has made. This coverage is the least negative. For instance, Thomas L Friedman wrote “The difference is starting to show. Just compare arriving at La Guardia’s dumpy terminal in New York City and driving through the crumbling infrastructure into Manhattan with arriving at Shanghai’s sleek airport and taking the 220-mile-per-hour magnetic levitation train, which uses electromagnetic propulsion instead of steel wheels and tracks, to get to town in a blink.”

For all the achievements, economic problems remain serious in China, such as the problem of rural development, environment pollution, etc. Thomas L Friedman thinks that “Chinese officials still put their highest priority on growing G.D.P. — their bottom line. But for the first time, the costs of this breakneck growth are becoming so obvious on China’s air, glaciers and rivers that the leadership asked for briefings on global warming”.

On the other hand, the Chinese awareness of existing serious problems and their efforts to remedy the problems also found their way into Thomas L Friedman’s reports. The following coverage are good examples: “Postcard From South China”, “China’s Sunshine Boys” , “China’s Little Green Book”.

4. Olympics

The coverage of the Olympics is the most positive. It is perhaps the only major subject about which the positive news greatly outnumbers the negative news.

“China has far outpaced United States in growth during last seven years since it has been preparing for Olympic Games.” He said that wealthy areas were more interesting, advanced and sophisticated than wealthy parts of United States, and attributes this to focus on building infrastructure.

He argued: “US could learn that big, long-term infrastructure projects require intense focus and followthrough(from China)”.

5. U.S.-China Relations

Through Thomas L Friedman’s coverage, we can find that when China’s economy was on high speed of development from 2005 to 2009, U.S.-China relations were very close. He insisted that China would become a “responsible ‘stakeholder’ in the international system.” He hoped that “China and United States can build partnership to address urgent issues of energy and climate change, which affect both countries.” In addition, he points out that nowadays is a “teaching moment” for both of the two countries, which are learning from each other.

Conclusion

This analysis clearly shows that Thomas L Friedman hasn’t been demonizing China. Apart from some sort of distortion of Chinese politics, his reports about China from 2005 to 2009 were more and more balanced.

U.S. domestic politics and culture are different from those of China. How Americans view these differences contributed to how China was portrayed in Thomas L Friedman’s reports. China has embraced the whole world nowadays. I am confident that if Thomas L Friedman really focuses on how ordinary Chinese people live, work, and worship, he will understand China more deeply, even Chinese politics.

Another interesting chat I had on May 4th was with my one of my teachers at Peking University. I was curious what a Beida teacher (who teaches Chinese to foreign students) would have to say not just about May 4th spirit today and PKU students, but the possibilities of discussing contemporary Chinese politics with her wards from overseas.

Here are the more interesting of her answers to my questions. On May 4:

- The new way of thinking after May 4th 1919 (democracy and science) was a bigger break from the past and did more for China’s progress than the Communist Party and its revolution achieved.

- “Protest is not the best way to solve problems now.” Also, because of the Chinese hobby of ‘watching the fun’ (kan renao), protests make small problems look bigger than they really are.

- She noticed the news story (in Chinese, Danwei coverage here) of Wen Jiabao visiting students in his alma-mater, Tsinghua University. As she heard it, Wen encouraged them to “join their ambitions with those of China … go to the countryside and work for China’s development”. She disliked the idea of students being told to think about serving the CCP’s interests above (she felt) their own.

On modern Beida students:

- “New [Beida] students think of work prospects. Before, they thought when will the foreign powers leave China.” [This again echoes what students told me themselves; it’s an opinion I’ve heard from more than one teacher and administrative staff worker in Beida.]

- “[Beida] students now are satisfied with the Chinese government. As for me and my generation, I’m not so satisfied.” [In class, before our conversation, she had grumbled about the one child policy, and used China’s wealth gap and corruption problem as examples with which to illustrate grammar constructions!]

On the freedoms she and her colleagues have to discuss such political and historical matters with foreign students:

- She thinks of herself as different to her colleagues who only discuss these topics in private. She believes in free exchange of criticism and opinion between China and the West. [is the West represented by students like me?! No pressure.]

- [I press her further] “No freedom” for teachers of foreign students to say whatever they like. The reason she gives: if a student’s opinion is their own, fine. If it’s received from their Chinese teacher, then the teacher could get in trouble.

Finally, a little postscript of my own: I attend a weekly lecture class at Beida for foreign students learning Chinese, called ‘Chinese culture’. Topics range from ‘tea’ to ‘China’s disabled population’ (see my second bit and bob here), to last week’s ’60 years of development in China’s countryside’. Any political discussion is all very open: the lecturer in that last one even mentioned the infamous ‘flying the airplane‘ torture – that link is unsurprisingly blocked in China.

However, I couldn’t help but feel a little propagandized on a couple of occasions (and patronized … ‘patrogandized’?). Nothing big: mostly the lecturer drawing attention to China’s overwhelming domestic problems and emphasizing how party policy is solving them in the right way. True as that might be, I think the role of a teacher is to give the facts, analyze them, but leave it to the student to make up their minds for themselves.

- The China Beat blog today republished my post about the Model UN, introducing this blog to their readers. Thank you China Beat!

- So Huang Yueqin, the director of the National Centre for Mental Health, has said that 100 million people, or 7% of China’s population, is mentally ill. That’s funny: in a recent Beida lecture aimed at foreign students, my teacher told us the total figure of all kinds of disabilities was 6.3%. Get your story straight. (And a response a Chinese friend wrote me on facebook to that 100 million statistic: “Let’s put another zero and it’s not far from the truth, hoho”.)

- I couldn’t resist putting up this clever illustration, from a Japanese blog:

Beida students arrested in the aftermath of the May 4th protests, 1919 It being the 90th anniversary of the May 4th uprising, I spent my lunchtime today sitting in the heat on Beida’s (PKU’s nickname) campus, chatting with students to see if they felt May 4th spirit was still alive in Beida today. I arrived just in time to see two men on a ladder unfurl – with distinct lack of pomp and circumstance – a banner reading, in Chinese, ‘Peking University commemorates the May Fourth movement’s 90th anniversary’. Besides them and a dozen lazing security guards, noone seemed to care.

Here are two representative comments from a young guy and girl (respectively) I talked with:

“Nowadays, students want to earn a lot of money, live a better life … gain knowledge to make themselves famous and rich. They’re not concerned too much for their country. Now society’s advantage is in harmony with individual advantage. If they fight for themselves maybe they will also benefit society.”

“Now, on the one hand because of economic development, on the other hand because of control of speech and failure in 1989, college students pay less attention to politics, are more individualistic, and pay more attention to their own career … I think [May Fourth] should be celebrated more publicly, but it is treated with indifference.”

This, remember, is the very campus where the May 4th movement was born (we won’t let technicalities like the fact that the university switched location from downtown Beijing to the far North-West in 1952 bother us, right?). Beida students – even a brief stay here backs up their self-diagnosis above – have changed from the likes which produced the politically outspoken activists of 1919 (as in the picture) and 1989. There is more to lose than ever before from shouting, more to gain from silence. The class of ’09 will be changing China from within its system, not from outside it with a banner in their hands.

|

|