|

Articles by alec

I live in Beijing and write freelance journalism as well as this blog.

Your humble blogger rises from the ashes for one last post before this (now very) old blog is archived for perpetuity, or until I forget to renew the domain license, whichever is the sooner.

I arrived in China on August 22 2008, two days before the Olympics ended (and I was there at the closing ceremony). I had backpacked through the country the summer before, teaching English at a Tibetan village in Qinghai province which I wrote about here, but now I was here to live and learn the language for two years, at Peking University. At that time I became interested in the generation of young Chinese around me, my peers, and started this blog as a way to keep up with six of their lives – mostly my friends on campus, but also an environmentalist and an entrepreneur.

Now, eight years later, after returning to China as a writer in 2012, my book Wish Lanterns is published by Picador in the UK today (and next spring in the US). It follows the lives of six young Chinese, too, and grew out of the seed that this blog planted. But it’s a different six – a wannabe rock star, a migrant addicted to online gaming, a Party official’s daughter, a fashionista, a netizen and a small-business owner – and has a wider scope, taking us from scorching Xinjiang to freezing Dongbei, from tropical Hainan to the outskirts of Beijing. You can find collected reviews and Q&As here.

In that respect, my mission is done. I set out to get under the skin of young China, back when I was another young arrival from the West. Now I’m thirty, and the generation of post-80s Chinese that was my beat are in their late twenties and early thirties too, giving way to the post-90s and (gosh) the post-00s: the next “generation that will change China”, in the words of my tagline. Even my blog that replaced this one, the Anthill, has closed its gates, and my new gig is editing the LARB China Channel while I look to the edge of China for my next big writing project.

Looking back, I remember fondly those first years, when blogging was young and exciting, just as China was in my fresh eyes. This blog is dead, but those memories still live.

I just couldn’t keep away.

For the last couple of years I have been in London, running literary interviews for the curation website Five Books. (China-related ones include Ma Jian, Orville Schell and Jeff Wasserstrom.)

Now I’m back for the long run, living in Beijing and writing freelance, as correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books among more long-term projects. I will also be blogging again – but not here.

My new space on the web is the Anthill. Whereas on this blog I followed the lives of six young Chinese friends for two years, on the Anthill I will be posting a more occasional and eclectic mix. The focus is narrative writing, which is the kind I most enjoy. There will be stories and snapshots from Chinese society – especially young China, ever my beat – but also fiction, satire, and oral history.

The Anthill is also an experiment in group blogging. It’s an “open blog”, where anyone can submit a story from or on China. So there will be posts from other like-minded writers too, alongside mine and edited by me.

So, please follow me at the Anthill (RSS: http://theanthill.org/rss.xml), and on Twitter @alecash, where I also post links to my articles elsewhere – like yesterday’s dispatch in the Economist from Tongren, or my profile of a Tibetan friend there which featured as a chapter in the book of reportage Chinese Characters.

Oh, is anyone there, by the way? If you still have this feed on RSS, dead wood for two years, your faith has been rewarded by one last hurrah! If you’re following a link, please do look at the archived posts below (my six most read posts are in the left sidebar), for a snapshot of student China from 2008 to 2010.

The blog is dead. Long live the blog.

UPDATE: [January 2011] After much umming and erring about whether to resurrect this blog from London, I’ve decided that I am too far away from China to be writing about it. But I will be blogging again when I’m back in the Orient, before too long a wait …

First things first: a couple of links. Here you can read my column in this month’s issue of Prospect magazine, on the influx of foreign students who – like me – go to Beijing to learn Mandarin. While here you can see my photo essay on ‘young China’ – the theme of this blog – for the China Beat. I took those pictures over the two years I lived and travelled in China.

“Past tense!” I hear you cry. “-ed?” Yes, I’m writing from London, where I will be based for two years before returning East. I thought I wouldn’t leave Beijing for love nor money, but one of those reasons is indeed why I’m back in Britain (you can guess which).

*

Next, here is where we leave the six young Chinese who I’ve been following on this blog – stories from the generation that will change China.

Ben is going strong in his online clothes shop. His bedroom business has expanded from just him and a leaky roof to a staff of three and booming sales. He still can’t pronounce the word ‘entrepreneur’.

Leonidas is back on “my island”, as he calls it, off the coast of Shanghai. “No TV, no internet, no noise, no traffic jam,” he writes me. A perfect summer break before his final year at Peking University.

Marie has finally ended her torturous job hunt, choosing a teaching position in Beijing. But she still dreams of working in Hong Kong, travelling to Japan, studying in America – depending on the day.

Matilda has just finished her novel, Summer Fruit in Autumn. She posted in online, and got some encouraging comments from Chinese netizens. She still doesn’t know what to do with her life, though.

Tony will be joining me in England next academic year. He has an offer from Cambridge and a provisional offer from Oxford, to read an MPhil in International Relations. I hope to see him before long.

William dropped out of university for the second time last spring. His lifeless subject and doctrine-heavy classes simply weren’t for him. He’s now decided to give his all to environmental activism.

*

Finally, a few quick stats and thanks. I launched this blog on the final day of the Beijing Olympics, August 24th 2008. Since then, I’ve had over 15,000 unique visitors. And 40,000 page views. My most read posts include a video interview with Chris Patten, commentary on the 20th anniversary of Tiananmen, a translation of a wronged student’s petition, and my essay in Chinese on China’s ‘New Youth’.

My thanks go first to all my friends, most of all to those I follow here, who have helped me understand the nuanced and changing story of young Chinese in a new China. In the English language Chinese ‘blogosphere’, an especial thanks to: Jeff, Kate and Maura at the China Beat; Jeremy and Joel at Danwei; Elliot at CNReviews; Charlie at China Geeks; Evan Osnos at The New Yorker. And everyone else!

Adieu to å… (liu – six). Cheers, Alec

In this week’s Economist, I have a short article on China’s budding greens – the new generation (my generation) of climate change activists who form student clubs and environmental NGOs. I’ve been hanging around these groups for the last two years, introduced by my friend William, who I write about on this blog.

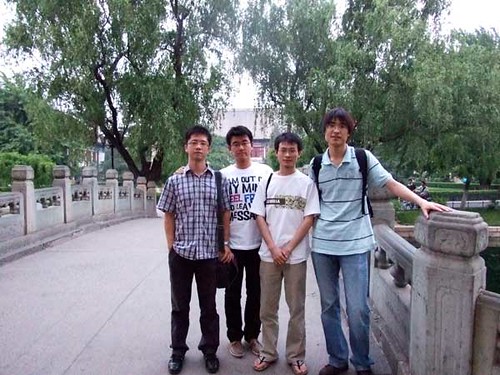

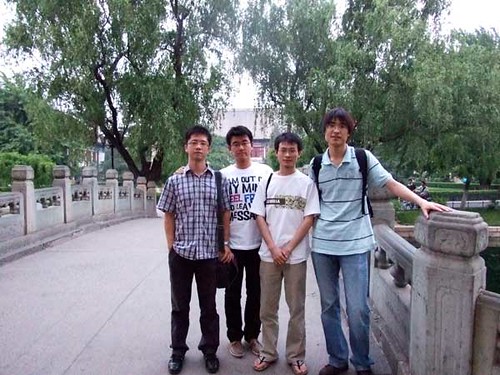

There was no picture with that slot, but the beauty of self-publishing is that I can upload a few here. In this photo, which I took just inside Beida’s West gate, are three members of Beida’s CDM club on the left, with William towering on the right.

I also write about the Beijing-based unregistered NGO CYCAN. Here’s their logo.

And their motto, ditan weilai qingnian zeren – “Low carbon future; youth promise”.

‘Promise’ could more literally be translated as ‘duty’ or ‘responsibility’. And only the future will tell if they live up to it. There’s plenty more to be written about this movement of the world’s most populous demographic – still ‘green behind the ears’ – to fight the world’s most pressing threat.

In late May and early June, I interviewed professors Zhang Weiying and Pan Wei of Peking University (known as ‘Beida’). I wanted to know what the generation who grew up in the Cultural Revolution thought of the generation who grew up in the Consumer Revolution – and who could be leading China in thirty years. Here’s what they said.

*

Zhang Weiying is at the forefront of the ‘New Right’. In (much too) short, that’s the school of thought in China which favours free markets and a clean break from socialism.* Or as Mao might put it, capitalist roaders. Zhang helped to pioneer economic reforms in China in the early 80s, and believes that a propertied class is the foundation of civil society. (“Ownership”, he told me, “is rather a responsibility and respect for other’s property.”)

I asked Professor Zhang if he thought Beida could become a world class university (it was only 36th in this 2007 ranking). His first comment was that in just thirty years in China, the number of students enrolling in college in a given year has multiplied by twenty (roughly 30,000 in 1978, when universities opened again after the learning-free zone of the Cultural Revolution; 600,000 in 2009).* And you expect Beida to be a world class university already?

He also mentioned government control in universities as a factor: Beida can’t diversify the curriculum without autonomy or academic freedom. But the problem runs deeper than that. Many of the faculty don’t encourage creativity in their students – the aim is rather to get the right answer (the “only one”). “New ideas are not encouraged. … If you go through this system,” professor Zhang continued, “you will become narrowminded.”

So is this what he thinks of Beida’s elite students, China’s future? No, of course there are bright sparks of independent thought (especially amongst his own students, of course…). But in the ‘post 80s’ generation as a whole, there is a worrying trend towards ziwozhongxin – self-centeredness. As the first generation of single children (the one-child policy came into effect in 1979), they “take everything for granted”.

One upshot of this, especially for the ‘post 90s’ kids who are not used to hardship (like the generation young during the 60s and 70s are), is that the pressure gets on top of them when they enter university or working life. Professor Zhang pointed to the spate of Foxconn suicides – all young workers who had joined the company just months before – as an example.

But he’s not despairing for China’s youth. After all, “they will grow up.”

*

Pan Wei is on the other side of the political spectrum, the ‘New Left’. He took his PhD at Berkeley, but back in China he was firmly of the opinion that China should follow its own path, not the West’s. His essay ‘Toward a Consultative Rule of Law Regime in China’** is an interesting, provocative read, arguing that democratic elections are an unsuitable model for China.

When I put the same opening question – can Beida become a world class university? -Â to Professor Pan, he rejected its terms. Beida is a world class university if analysed within a Chinese framework, using China’s criteria. (I have to disagree: it really isn’t.) Assessing China from a Chinese perspective – and ideally using the Chinese language – is essential to him.

That’s why – I know I’m digressing – the NPC or renda shouldn’t be thought of as a ‘congress’, according to Professor Pan, because the term paints it as an organ of a Western political system, and so it inevitably comes across as a “rubber stamp” to Westerners. ‘Civil society’, by the same token, isn’t “suitable” for twenty-first century China. Rather, the danwei – work unit - and jiating – household/family - are.

A bigger problem at Beida that Professor Pan identified was the declining number of students from the countryside. According to him, 70% of PKU’s students were from rural areas in the 1950s. 60-70% in the 60s. Today, the number is less than 1%. I can’t check that figure – Chinese universities are secretive about figures which would be public in Britain – but the trend itself is certainly incontestable.

Onto youth. Professor Pan echoed much of what Professor Zhang said. Young Chinese, single children and without the history and suffering of his generation, “become weak”. The same memes of “individualistic” and “psychologically vulnerable” came up. Also an astute comment, I think: that, on the whole, they aren’t interested in their parents’ history (more so in their grandparents’). But you could rephrase: the problem is that parents aren’t interesting in relating their history to their children.

Another result of their upbringing, Professor Pan told me, was “nanxing de nuxinghua” – boys becoming more like girls (or at least “zhongxinghua” – their neuterisation). A boy who is loved excessively (ni ai) can’t fight for himself. At this point, he declared that this results in more homosexuals. This, I should say, was delivered in the spirit of observation not prejudice. I see no factual basis for it.

IÂ won’t comment, expect to add that Professor Pan also said something intelligent: that older people have always had issues with the younger generations.

___

* for a better description, Mark Leonard describes New Right and New Left, as well as profiling professors Zhang and Pan, in his book What does China Think?

** in Debating Political Reform in China, ed. Suisheng Zhao

It’s summertime, the PKU campus has been alternatively balmy and sweltering, students are finishing up their exams, and it’s the season to buy cheap cherries. Add the final ingredient of testosterone, shake well … you get where I’m headed. Love is in the air (along with the potentially fatal pollution particles).

A bashful Brit, I’ve always been rather shy when it comes to talking about love and sex with my Chinese friends. But I pale in comparison (unintentional pun) with their own willingness to broach the topic. There are some questions which will only illicit a blush or an awkward brush-off. When I asked Marie if she had a boyfriend (she doesn’t), she gave new meaning to the phrase ‘red China’. Physical contact like hugs is no-go territory. And I’ve seen none of the ‘conquest’ bravado between guys at Beida that there was, for instance, at Oxford.

But does this mean there’s no sex on campus? Of course there is! As there is on every bloody campus. It’s obvious from anything from a quick kiss in the canteen, to the playful groping-slapping game of couples on the subway. But this ‘less sex than the British’ idea about China’s ‘army of heterogenous youth’ is as false as it’s magnetically opposite stereotype: that young Chinese attitudes towards sex are now exactly the same as American or ‘Western’ ones.

Matilda was telling me about dating culture in Beida, over a tea/coffee (respectively) in the university’s ‘Café Paradiso’. I asked if you could ask a stranger on a date here, like they do on TV in Friends. She loves the show, and remembered being surprised at American boldness in that respect. If someone pulled a stunt like that here, she said, “I’d think he’s crazy”.

Most Beida students are in a relationship, she said – half with students here, half with “people outside”. And the most common way of finding your partner was online, on BBS (Bulletin Board Systems, wildly popular across China, and especially so on campuses). I asked how that worked. A bit like this, she said, launching into what she considered a typical relationship-in-bud:

1. A guy posts an article on a popular college BBS (his opinion on a current affairs story, a composition, a rant, whatever).

2. Other students comment on his post, and the guy notices one particular (female looking) ID who has responded positively.

3. The guy contacts the girl, she writes back, they exchange QQ numbers (China’s MSN-like instant messanging service).

4. They chat online for anything between one day and one year before deciding to meet up and beginning to ‘date’.

5. After half a year or so after meeting, they sleep together. (NB this could also happen on day one, but that’s unlikely.)

Don’t think of that as a ‘model’ … it’s just Matilda’s account of a run-of-the-mill romance. There are love at first sights and one night stands, too, although the most common ‘how we met’ story I’ve heard over the last two years is the perennial tale of ‘classmates … slowly friends … then …’

That’s not unlike how Matilda and Leonidas first got together. Matilda had broken off with her long-time boyfriend because they shared no common interests, no real communication. She was arts; he was computers. But with Leonidas, she could discuss classical Chinese poetry and the linguistic theories of Noam Chomsky. I remember when she first introduced me to him, two autumns ago, in the first flushes of excitement at their relationship.

It didn’t last. Matilda’s version is that they had no connection at a deeper level; Leonidas’ is that she talked endlessly about, and with, her old boyfriend. Both are likely true. Now Leonidas is a dashing bachelor once more, and Matilda is back together with the ex, complaining again that they have nothing in common. But he loves her, and she clearly loves him.

Of course, there’s a whole back-story to that relationship itself, with twists, turns and a lost love, all worthy of Matilda’s novel. But it’s not for here.

|

|